Dallas Art Fair

Merrick Adams, Deborah Brown and Roscoe Hall

November 12 – November 14, 2021

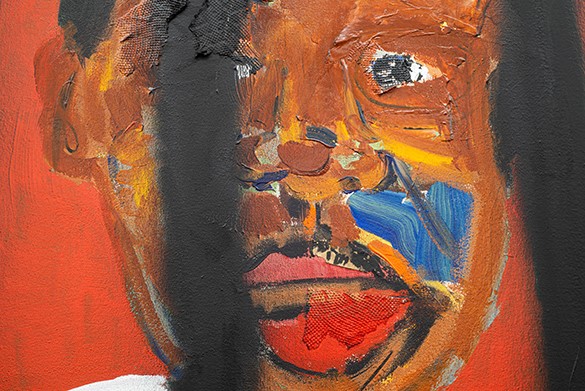

Roscoe Hall

Stepping into Roscoe Hall’s immersive triptych End Where You Start, you can almost hear Joe Strummer singing, “Clang/Clang/Go the jail guitar doors.” Hall may well have had that very tune banging out of his studio speakers while crafting this life-size work. This triptych — the next chapter in Hall’s slow reveal of the misperceptions and misconceptions surrounding Black life — is a scathing critique of the prison industrial complex.

End Where You Start reads like a map, his backgrounds color-coding inmates in the same ways that prisons of every type reduce humanity to shade: sure, stripes may appear less frequently, but in their absence we see colors including pink (pause for a moment to consider how this traditionally feminine tone is used to emasculate inmates), the familiar jumpsuit orange, red (high-risk), white (death row), green (low risk), and more. Rather than adopt this sartorial disempowerment, Hall prefers the subtler approach of situating his subjects within an overarching background.

With End Where You Start, Hall challenges our expectations, connecting every inmate directly with the viewer, placing us in complex yet undefined roles: guard, visitor, fellow inmate. Where his work particularly resonates is in its ability to displace our expectations of large-scale representational works. This is no Night Watch, no venerated altarpiece, no Renaissance romanticism. We’ve stepped through the metal detector, emptied our pockets, and are now standing in proximity trying to discern where we belong. We see white shirts, khakis, and grey/black pants, and what looks like that ubiquitous prisoner ID bracelet.

Formally, Hall pulls no punches – cell bars are rigid, formal, dissecting a face, hiding expressions, being pulled against…futilely. Less apparent is the combination of motion and emotion – the consistency of the beltlines, the flow of the bracelets, the impressions of depth, the bars seemingly surging off the canvases. Maybe the simplest approach would be to consider the dialogue between Charles Dodd-Blakley and Anniston Bennet in Walter Mosley’s novel, The Man in My Basement: “I need a black man to look in on me. No white man has the right.” Here, perhaps, we have the right — but the question of what exactly is right is something else entirely, brought to life in the differences and consistencies Hall has mapped across his canvases.

Roscoe Hall is a painter living and working in Birmingham, Alabama. He received his B.F.A. in photography from the University of San Diego and his M.A. from the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD). Hall’s works have been exhibited at the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum, Savannah, GA; Graeter Art Gallery, Portland; Lowe Mill Gallery, Hunstville; and the Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA), Birmingham.

Roscoe Hall

End How You Start, 2021

72 x 180 x 2 inches

Acrylic, Pastel, Ink, Paper Towels, Hybrid Sativa & Indica, Hennessy, and Anita Baker

Triptych, each panel 72 x 60 inches

End How You Start, (Detail)

End How You Start, (Detail)

End How You Start, (Detail)

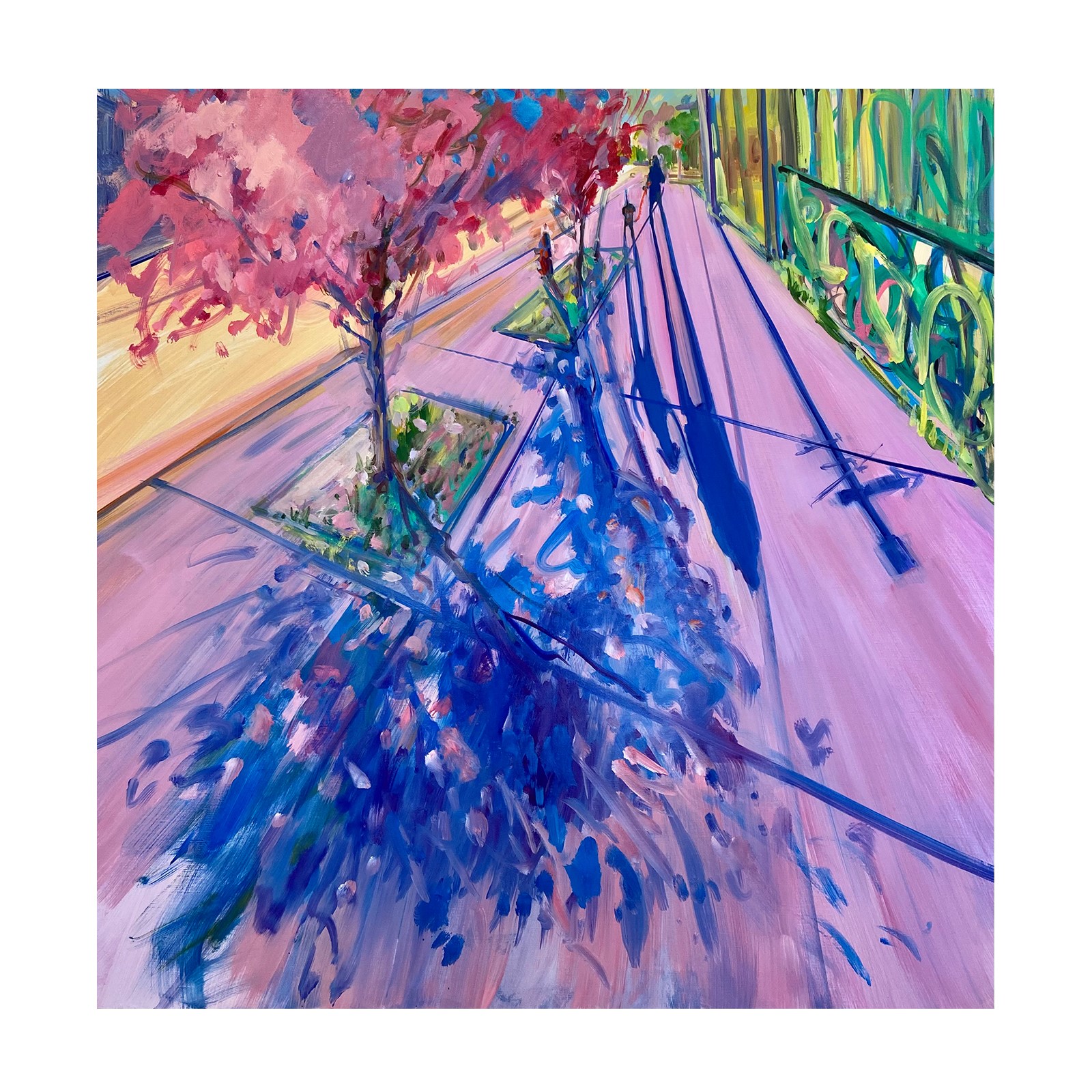

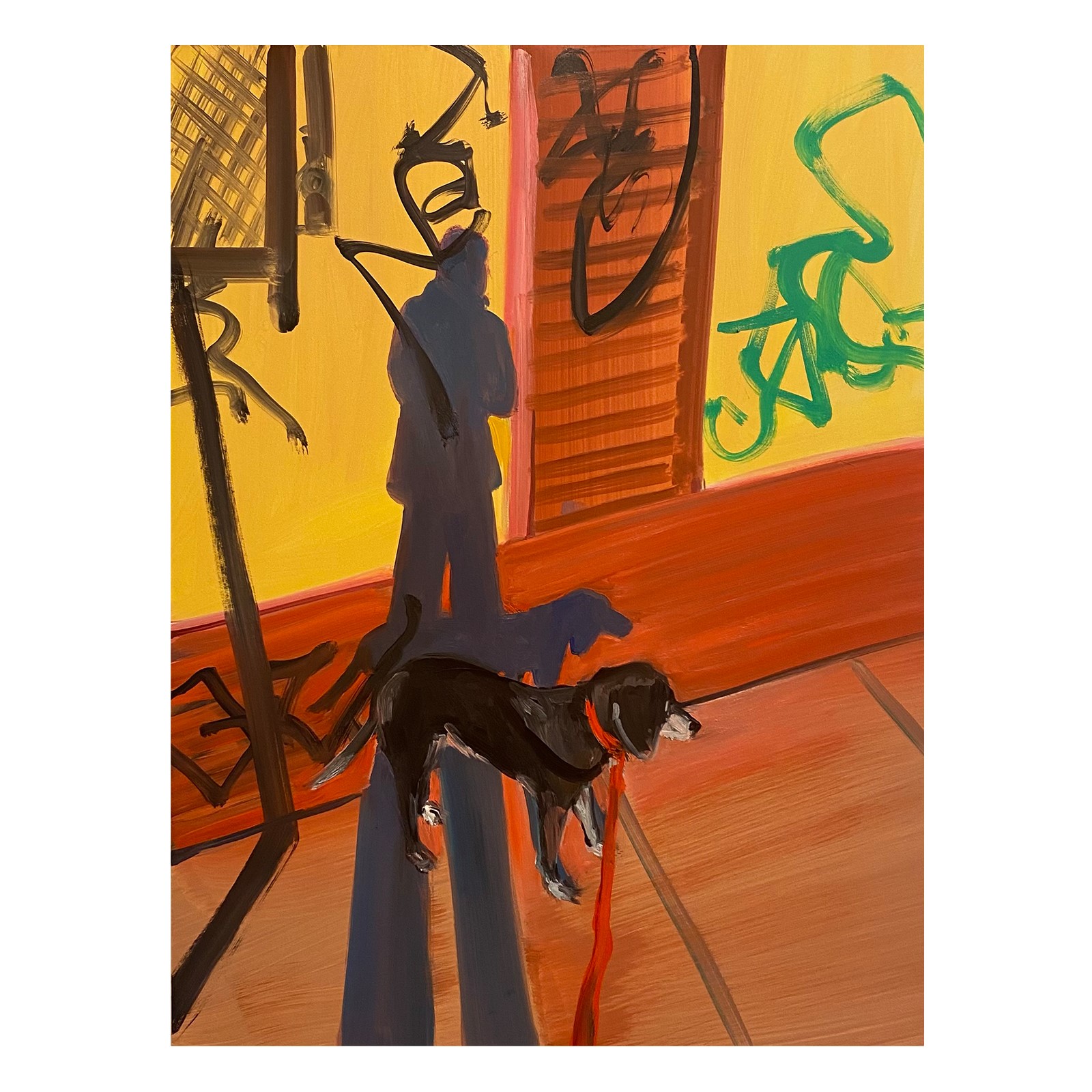

Deborah Brown

Shadows are oscillations. Not merely of light, but of existence. A shadow is the two-dimensional assertion of existence stripped of all its identifying characteristics. Shadows are the same color; the same dimension; the same duration. What differentiates shadows, or at least what should, is their creator – shadows as the ephemeral manifestations of identity.

Deborah Brown grasps these nuances in her Shadow Paintings, foreboding yet foregrounding our shared experiences over the last year. Solitary walks in formerly familiar places, accompanied only by her dog, who can tell but not say. This duality, presence and absence in the same moment, has defined us all during this time. What makes Brown’s paintings resonate even more is her willingness to strip individuality from her works in the service of our subjectivity, each long shadow streaming across the canvas a placeholder for us all.

Of course, the dog is our faithful companion, making regular appearances throughout art history. As well as leading the way in Gustave Caillebotte’s Le Pont de l’Europe, they appear in works as diverse as those by David Hockney and Andy Warhol, who shared a penchant for dachshunds, as well as in works by Lucien Freud, Frida Kahlo, and more. The dog art pièce de résistance, echoed in Brown’s implied motion, may well be Giacomo Bella’s 1912 Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, its futurist legs a staccato blur racing across the canvas.

What makes Brown’s work particularly unnerving is perspective—each of us both casts the shadow and is behind the person casting it, the emptiness sprawling out ahead. She then situates us, geolocates us, places us in proximity. Stagg Street. Siegel Street. Maybe it was a loop down Bushwick Ave. Whatever the case, Brown immerses us in site, in place, in space, on a walk across the desolate heart of Williamsburg. Then, she immerses us in her recollection, on canvas, in paint, deep blue and gray and green and purple shadows against a bright red leash.

In a time in which depictions of urban isolation seem to have shifted from painting to photography to sculpture and back—think Edward Hopper to Lee Friedlander, Louise Bourgeois to Mary Cassatt—Brown’s works draw us into space and time in the same moment that we move through her depictions of a pandemic-emptied, barren urban landscape. Perhaps absence is optimism, unlimited potential, the shape of the Empire State Building rising across the East River. Who knows? All we can hope is that Trout, and whoever is on the other end of the leash, got home safely.

Deborah Brown is a painter living and working in Brooklyn, New York. She received her B.A., summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, from Yale University, and her M.F.A. from Indiana University. Her works have been exhibited nationally and internationally, at the Hall Art Foundation, Schloss Derneburg Museum, Germany, as well as in exhibitions at galleries including Scott Miller Projects, Birmingham; Anna Zorina Gallery, New York; Unit London, UK; The Lodge, Los Angeles; Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art, Houston, TX; Lesley Heller Gallery, New York; BravinLee programs, New York; Galleri Christoffer Egelund, Copenhagen, and Angell Gallery, Toronto. Writings on her work have appeared in The New York Times, Art Forum, Art in America, Juxtapoz, Artillery Magazine, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, Observer, ARTnews, Artnet, Galerie Magazine, Hyperallergic, ART-Das

Kuntsmagazin, and more. Brown has been a visiting artist and lecturer at a number of universities and institutions including Penn State University, Hunter College, Pace University, Columbia University, Maryland Institute College of Art, Yale University, and Art Omi.

Deborah Brown

Blue Shadow, 2021

48 x 48 inches

Oil on Canvas

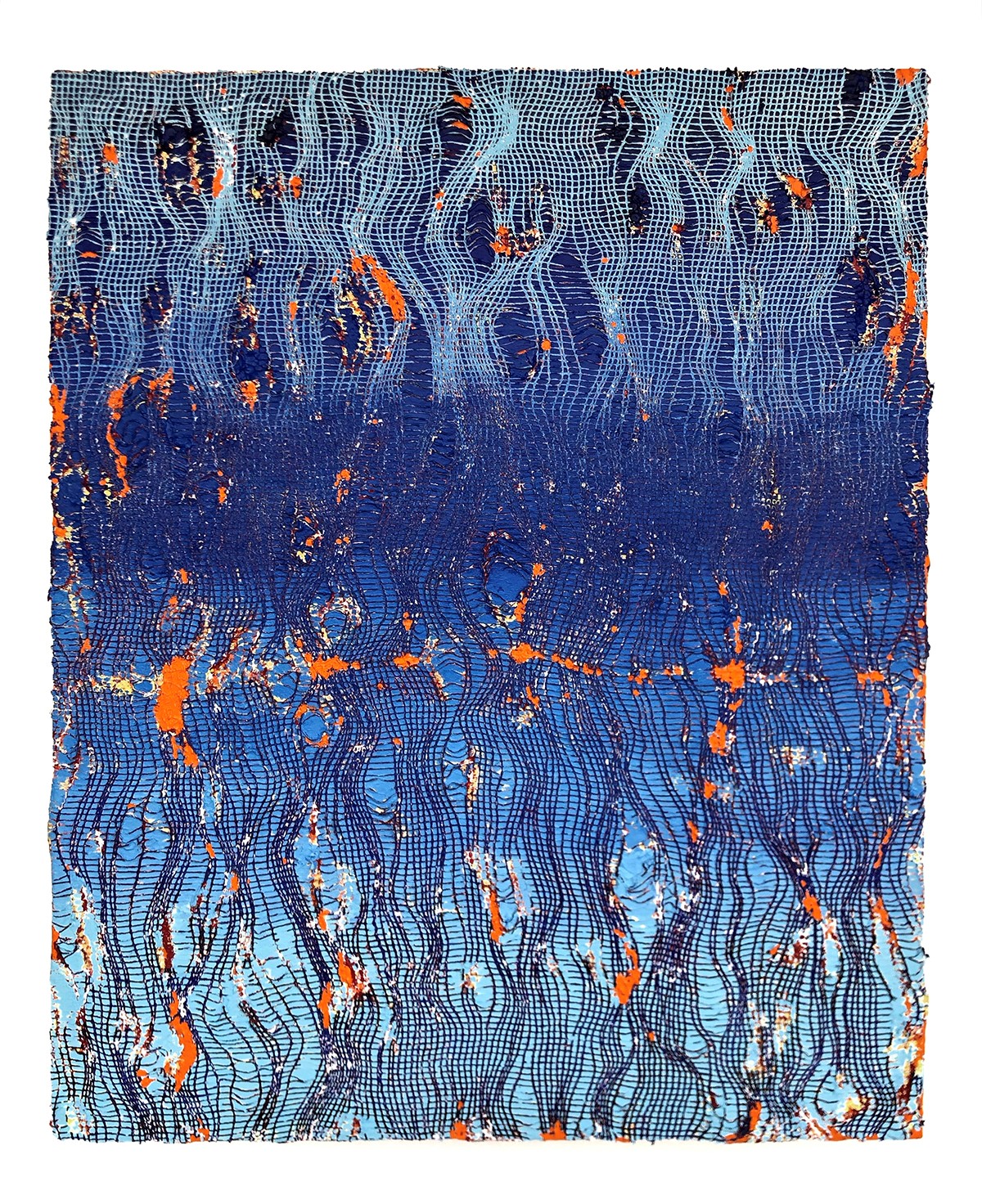

Merrick Adams

Map the dimensional history of art and you’ll see a consistent pattern: flatness to volume to flatness again; map the pictorial, and you’ll see one dimension, then three—thanks, Brunelleschi—then some aesthetic combination of the two. Figuration. Abstraction. Each time, the rules which govern our visual experiences change—well, more truthfully, they’re reinvented, with signposts that serve to assure us that our analytical and interpretive capacities haven’t changed.

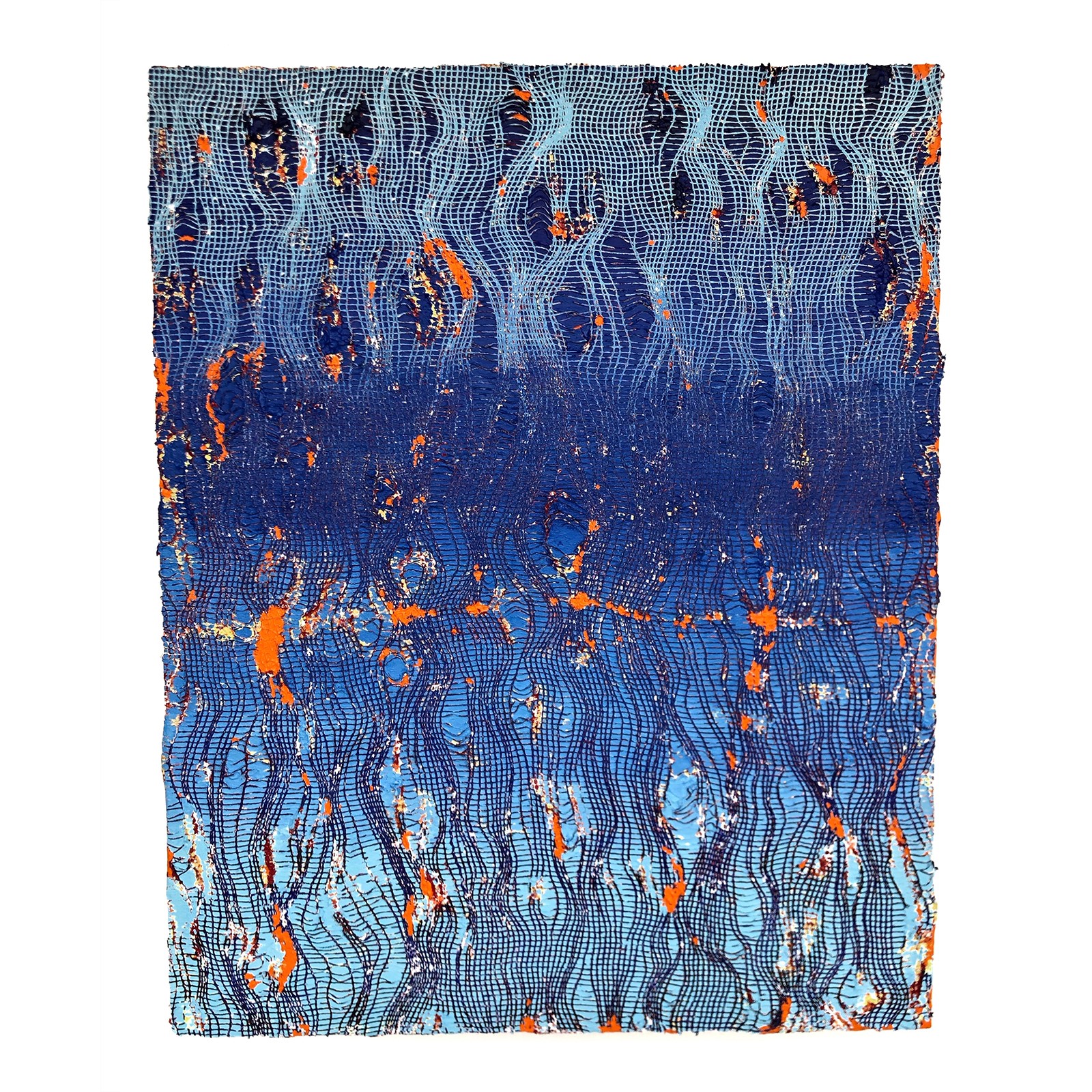

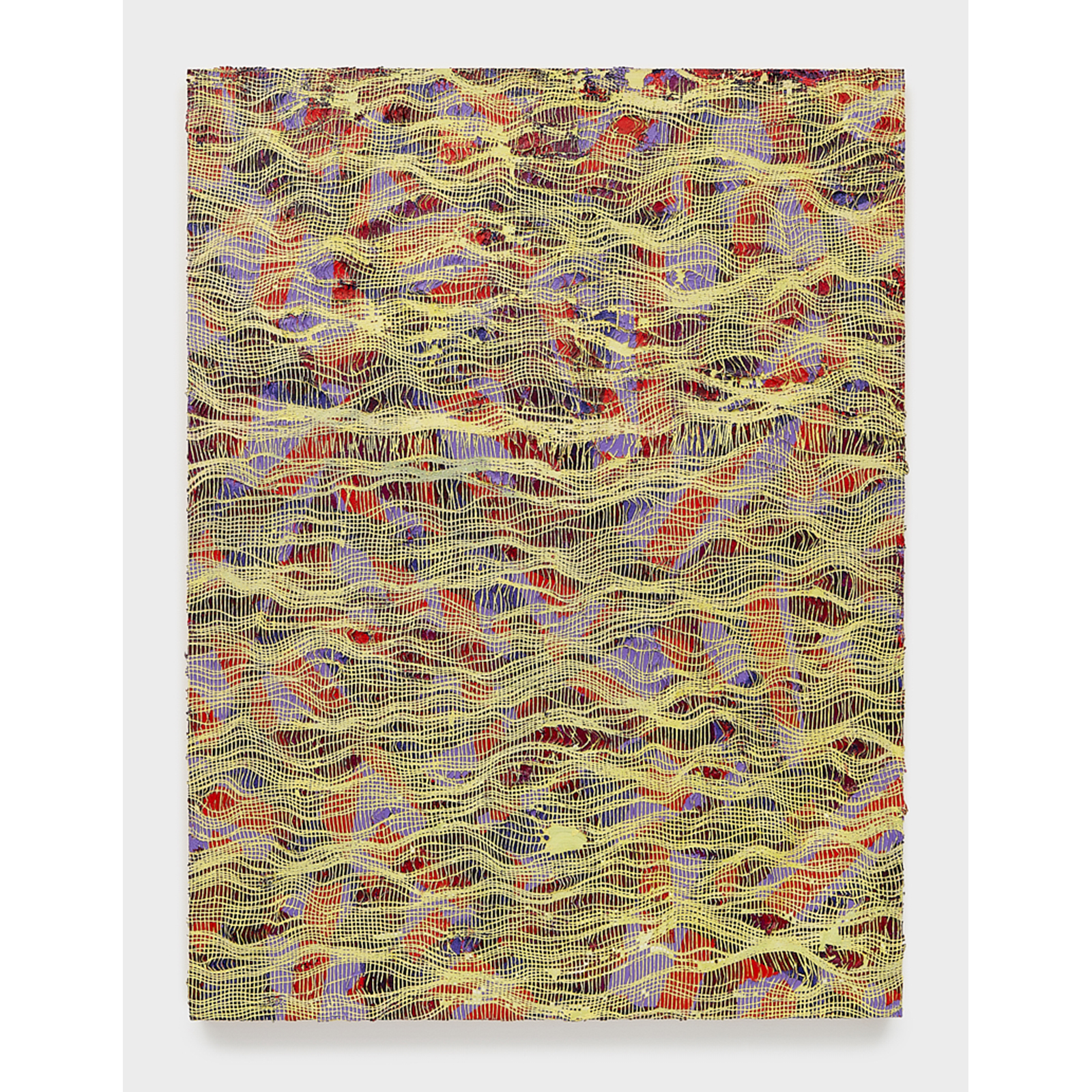

With painter and printmaker Merrick Adams, we find invitations anchored in suggestion and reference: quasi-familiar shapes, semi-recognizable names, that map a journey between materiality and surface. Much like we see shape and pattern come into focus from our airplane window, in Adams’s works we encounter ground materializing into surface. Plastic netting serves as a matrix, imperative and elemental, bringing pattern to field and ground. But the netting serves merely as Adams’s plate—demanding that he deal with its forms, inviting him to explore its interconnections.

Again and again, Plastic Camouflages become fragments and foils, meanings and markers, connecting time and location with a more complex encounter—plastic, here metaphorically both the topography of site and the detritus of existence. Dissolving into waves and currents, the plastic dissolves into the aesthetic, each surface demanding that we reconcile content and context. Seen at scale, Adams’s works require even more, fragments clinging to the paintings’ edges like plastic clinging to the shore.

One of the great aspects of sublime art is its potential to transform our understandings without declaring its intent. Adams’s works become sublime in their ability to entice us, to capture viewers in their beauty, the more subtle implications declared, but not declarative. As enticingly, Adams is a cartographer of the visual, speeding down west coast roads gazing toward fire in the sky, or into the summer paradise of a sunrise on the lily pond.

While contrary to traditional perceptions, Adams work is as aligned with Anselm Kiefer’s large-scale figurations as he is with any pattern and repetition abstractionist. Perhaps, even more. While he doesn’t compel us to walk or fall into constructed perception, each of his works is an undulating advance and recession, an optical displacement. Neither still, nor particularly soothing, Adams’s takes the energy of necessitated action and combines it with an invitation to simply stop and consider.

Say what you will, but as Adams’s filaments flutter, I think only of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass:

“And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones

Growing among black folks as among white

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same,

I receive them the same.’

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.”

Step close, and let Merrick Adams guide you on your way.

Merrick Adams is a Los Angeles-based painter and printmaker. His works examine our experiences of space and environment, as well as nuanced explorations of person and psyche. Highly regarded for both his figuration and abstraction, Adams’ works tread the complex space where they intersect, sometimes alluding to figure and form with only the slightest gesture. Adams holds a B.F.A. in printmaking, and an M.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

Merrick Adams

Burn This House, Burn It Blue, 2021

30 x 24 inches

Acrylic on Panel

Roscoe Hall

72 x 180 x 2 inches

Acrylic, Pastel, Ink, Paper Towels, Hybrid Sativa & Indica, Hennessy, and Anita Baker

2021

Roscoe Hall

48 x 60 inches

Acrylic, Pastels, Burlap, Sencha Tea,

High Life, and Hybrid Indica

2021

Deborah Brown

48 x 48 inches

Oil on Canvas

2021

Deborah Brown

48 x 48 inches

Oil on Canvas

2021

Deborah Brown

60 x 48 inches

Oil on Canvas

2021

Deborah Brown

60 x 48 inches

Oil on Canvas

2021

Deborah Brown

Dead End

24 x 18 inches

Oil on Masonite

2021

Deborah Brown

24 x 18 inches

Oil on Masonite

2021

Deborah Brown

24 x 18 inches

Oil on Masonite

2021

Merrick Adams

Burn This House, Burn it Blue

30 x 24 inches

acrylic on panel

2021

Merrick Adams

Fuchsia Voodoo

30 x 40 inches

Acrylic on Panel

2021

Merrick Adams

Plastic Camouflage: Fire in the Sky

36 x 48 inches

Acrylic on Panel

2021

Merrick Adams

The Sea Before the Sun

30 x 40 inches

Acrylic on Panel

2021

Merrick Adams

Plastic Camouflage: Sunrise on the Lilly Pond

36 x 48 inches

Acrylic on Panel

2021