Perhaps it’s this tendency which makes Ted Lawson’s works so sophisticated and sublime. While his materials list might suggest otherwise – laser-cut aluminum and industrial paint – his true poetics is anchored in processes of reinterpretation and manifestation. You see, Lawson begins with an ephemeral object, an 8 ½ x 11 sheet of art paper, which he then deconstructs with a single pair of scissors, the outcome totally driven by mood. The goal? Exploration. The process? Imagination, coupled with a deep distrust of the representational – that very quality that would seek to define what he does. “It’s a compulsive approach,” he explains. “Certain things trigger a need to continue.”

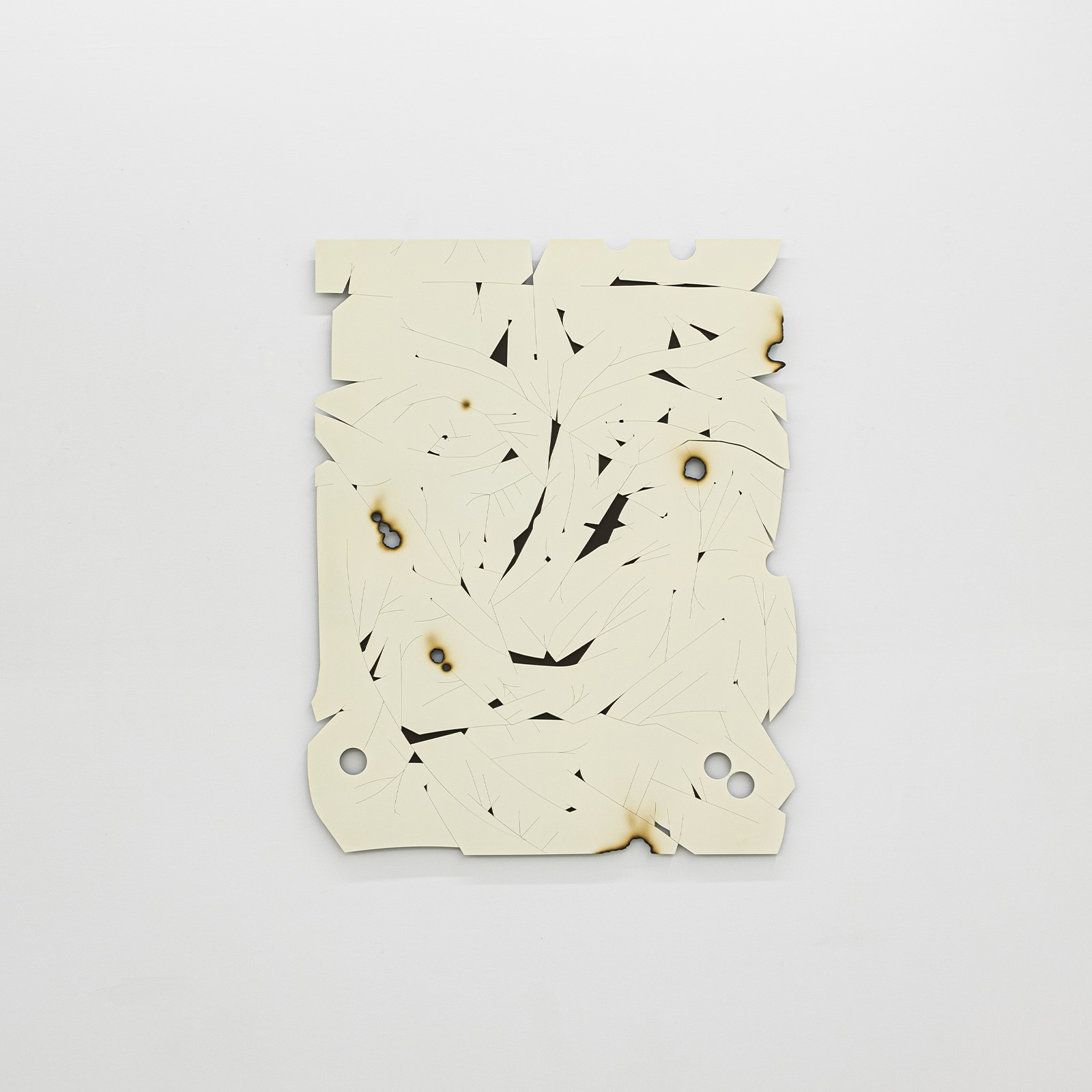

When you first see Lawson’s cut drawings, you’ll likely teeter just on the edge of trying to transform them into a definable object, something that aids in the transformation from pure expression to intended meaning. Yet Lawson sees this tendency as a danger. Precisely at the moment that he sees a pattern emerging in his cuts that make the work seem too much like something else, he ruins it. Not, of course, the paper itself, but its emerging narrative. Then, when he meticulously translates fiber to metal, paper to aluminum, through a series of vectors in a design program, he compels viewers to reflect on their understandings and expectations of both drawing and sculpture as mediums, and how he’s deflecting the meanings of both perception and expectation. That thing – a familiar piece of paper – has both transformed and remained, has become something else at precisely the same time that it has retained its primary surface form, intention, and meaning. Add in the painterly approaches to destruction and fragmentation – what looks like burns on the surface, or techniques to suggest a torn edge – and you force yourself to invite at least the possibility that there’s no difference between where Lawson began and where we now are.

Still, the works in Sol Invictus aren’t strictly allegorical, despite their titles: Book of the Dead; Head of Zeus; Pink Venus; Sol Invictus; The Cave. Rather than referring to or inferring something specific, Lawson allows whatever interconnections his titles invite to emerge through the process. “I create like it’s a movie, but I only have a fragment. Then, I start to see a story in it. The titles come last.” They serve more as invitations, as wayfinders for potential entry points into personally constructed narratives. Neither work nor title serve as end goals, but rather each stands as related, one to the other, without necessarily the need for both, because, as he explains, he begins as every work’s intended audience. Still, every show tells a story, and every work becomes a chapter in that book.

And, while there’s no expectation that any works produce a particular interpretation, Lawson begins from the position of our shared histories and experiences with their accompanying, familiar inferences. Mother, father, son. Zeus, almighty god of the ancient Greeks. Book of the Dead (though you might ask, “Egyptian or Tibetan?”) From consciousness to a beyond. “We know ourselves and the world from within ourselves,” Lawson explains, “so my interpretation of how these align is important to me.”

Step back from Lawson’s surfaces and you’ll see an invitation. Not so much one that requires a response, but one that requires merely the acknowledgement of similar perceptions. That it is not so much what is shown as it is the process of showing, just as it is not so much what is seen as it is the practice of seeing. Look back toward any of Lawson’s works, and ask yourself, in the spirit of Socrates, “Which would you rather believe – the idea of a cut piece of paper, or the manifestation you see?” Crumple the paper, twist it, fold it, tear it – but not fully apart – and you’ll find a page to write your version of an allegory that Ted Lawson invites you to share.

Ted Lawson

Head of Zeus

48h x 37w x 1d inches

Painted aluminum

2023

Ted Lawson

Pink Venus

48h x 37w x 1d inches

Painted aluminum

2023

Ted Lawson

Sol Invictus

46h x 39w x 1d inches

Painted aluminum

2023

Ted Lawson

Book of the Dead

48h x 72w x 1d inches

Painted aluminum

2023

Ted Lawson

The Cave

48h x 68w x 1d inches

Painted aluminum

2023