One of art’s most nuanced capacities is its ability to shine a light where we’re usually afraid to look. In music, that can be anything from Kendrick Lamar to John Lennon, in film, from Spike Lee to La Dolce Vita. And, if you’re looking for someone to add to the canon of sophisticated creative commentary, look no further than Roscoe Hall.

For his debut solo exhibition at Scott Miller Projects, Hall mines his own personal history: his crack-smoking uncle; his grandfather, the godfather of Dreamland; and Hall himself, trained as an art historian — he has an M.A. from SCAD — but renowned as an artist who has more than a little tendency toward sarcasm and the ironic.

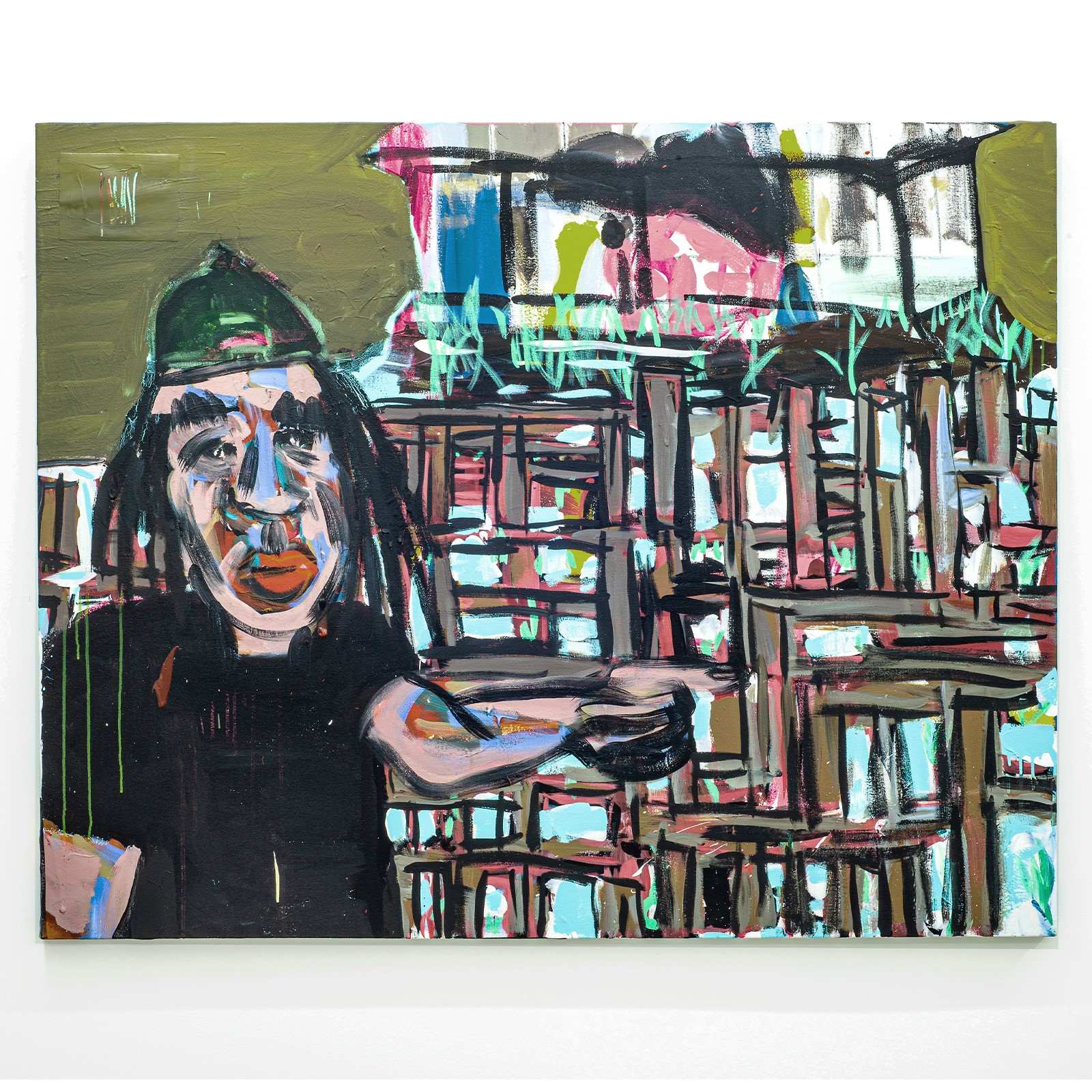

But this is no foray into another heart of Alabama folk art by an imaginative and talented Black artist. Far from it. At its simplest, Hall’s debut show is about what he terms “catching a bad deal. Whether it’s on the street or in the kitchen; it’s about all the ways of life that can crush a society.” Hall achieves this with touch, with the ability to blur the lines between flat, almost sequential-art style surfaces, and his preferred approach, which is highly textural. It is as if the 1980s have come alive again, reanimated in the form of Hall, who draws as much on the history of German neoexpressionism as he does on graffiti or folk art.

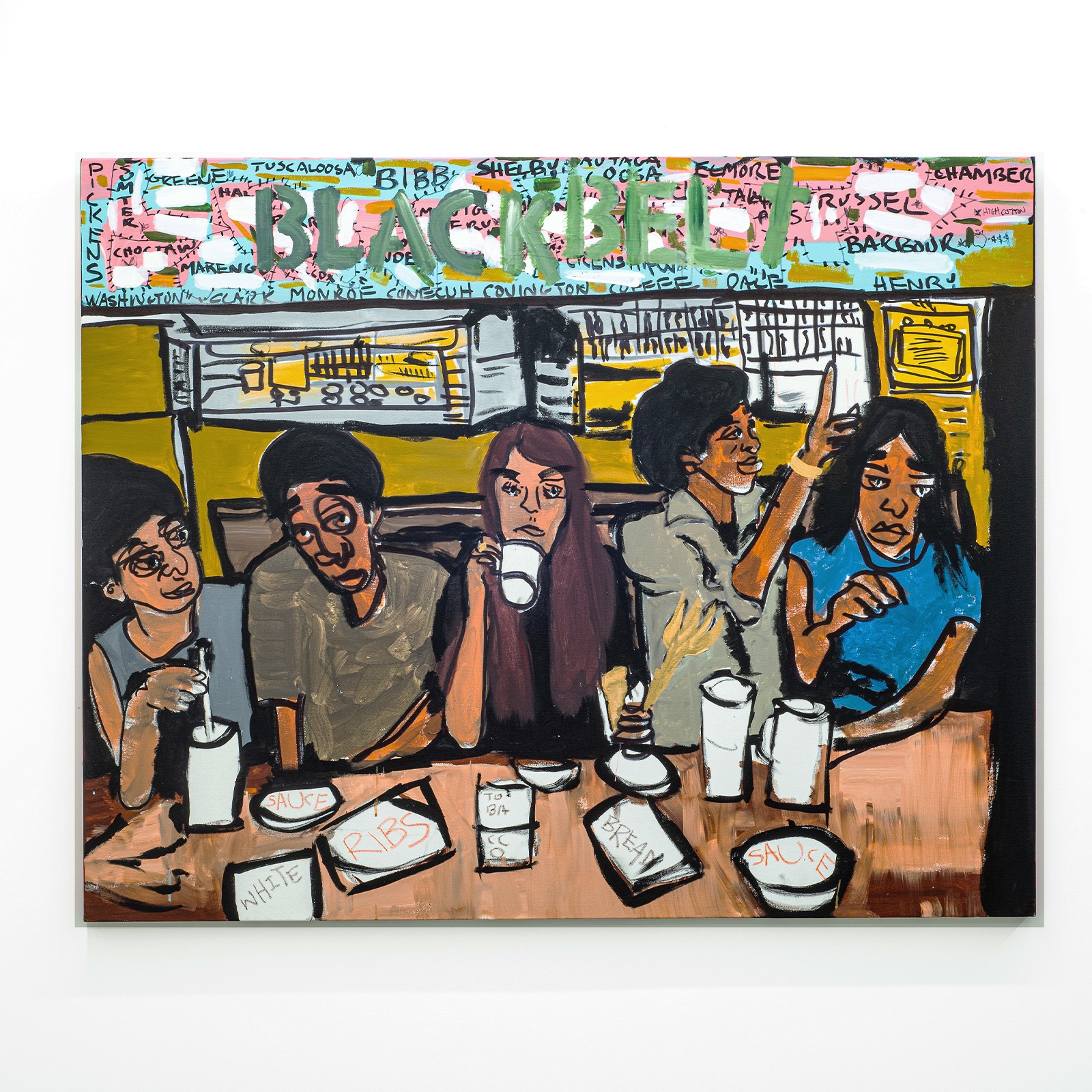

This show also marks a new approach, as Hall has pivoted to more traditional surfaces and supports. “I don’t usually work on canvas,” he laughs, “but that seemed to be what to do here.” Pair this approach with the scale – works more than four-by-six feet, and viewers can truly immerse themselves in the vignettes of life Hall creates – not that you might want to. There’s Alabama Black Belt, a multiracial moment captured in a diner, depicting the first time Hall ever dated interracially. There’s the portrait of his grandfather, which he’s titled NO FARTING – if you know, you know. There’s Jerusalem Heights, where his mother lives. And there are those untitled works, those prison bars, those moments that might make you take a step back.

What separates Hall from many others is his ability to develop layers, whether through texture on a work’s surface or through seemingly unexpected connections. That “Crenshaw” emerging from a sea of county names in Alabama Black Belt is, sure, a reference to one of Alabama’s “high cotton” counties, but it could just as easily relate to the sound of Dr. Dre and early NWA rolling through Compton and South Central, along Crenshaw.

Hall’s works are confronting without necessarily being confrontational. They’re referential as much as they are reverential. And they’re clearly meditations on his Black experience. They’re as much a map of his and his mother’s journey from Chicago to Alabama to take over the family business as they are signposts or markers on a multi-hyphenate life: artist, chef, father, husband, musician, punk, irreverent iconoclast. If you take anything at all away from these seven works, it is that they are as connected with Hall’s being as they are about how it is to be, and particularly, to be Black. The fact that Hall is working on such a large scale is an inference to how important these stories are in his life. Imagine that every mark on a surface is a word, and the larger he works, the more detailed a story he has to tell.

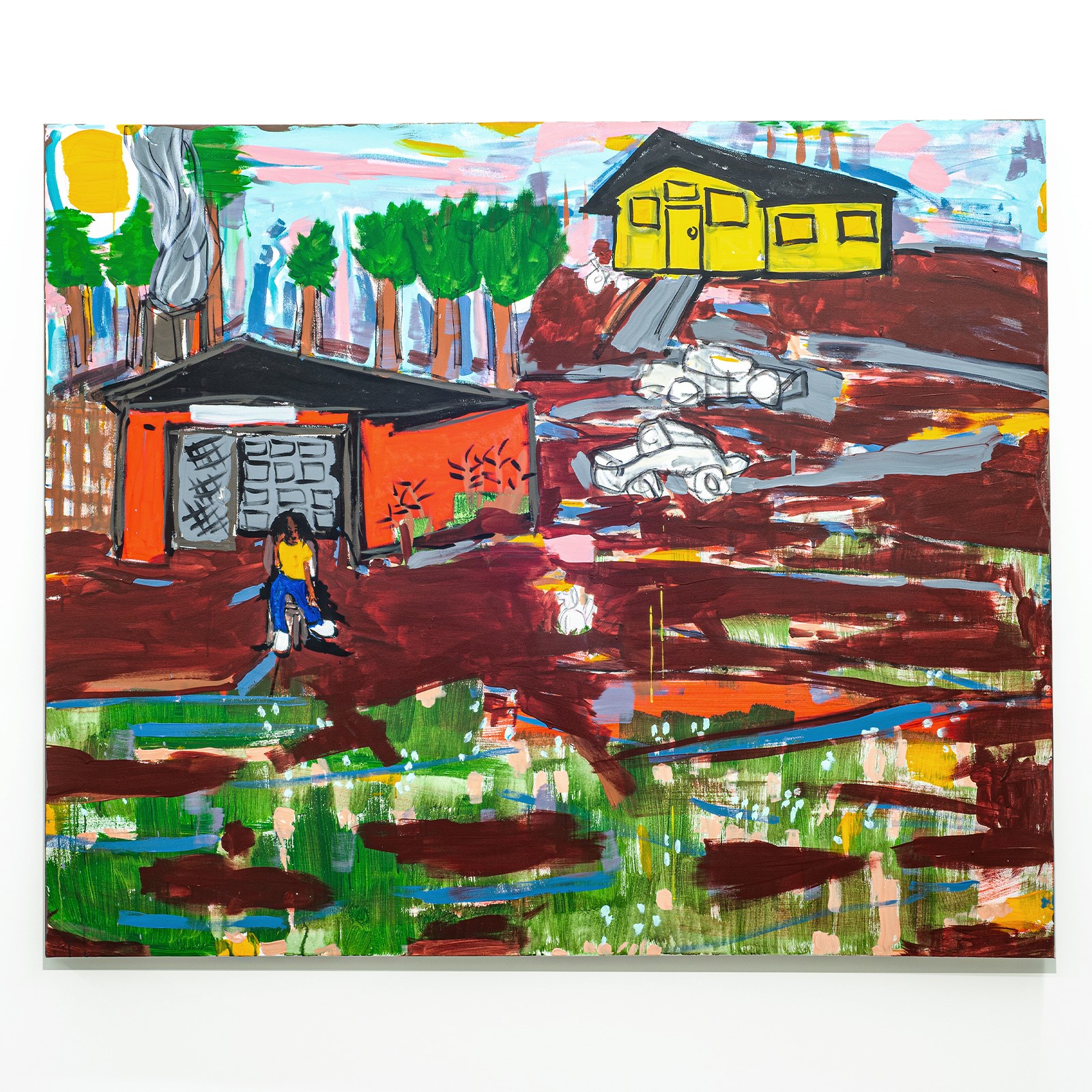

Roscoe Hall

Jerusalem Heights

60 x 72 inches

Acrylic, pastels, charcoal, spray,

new Drake album, orange wine, and Indica

2021

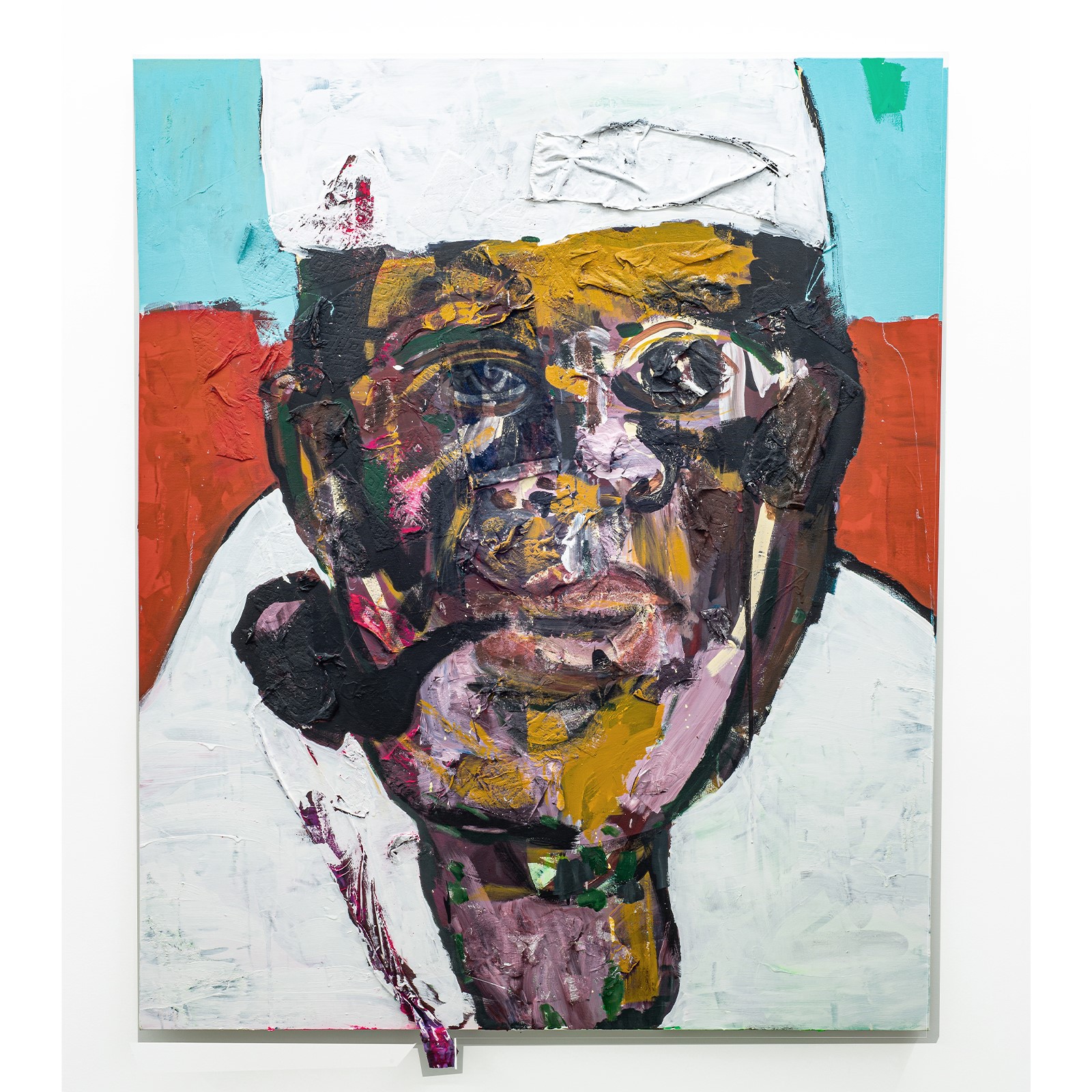

Roscoe Hall

No Farting

72 x 60 inches

Acrylic, paper, denim, charcoal, and Sativa

2021

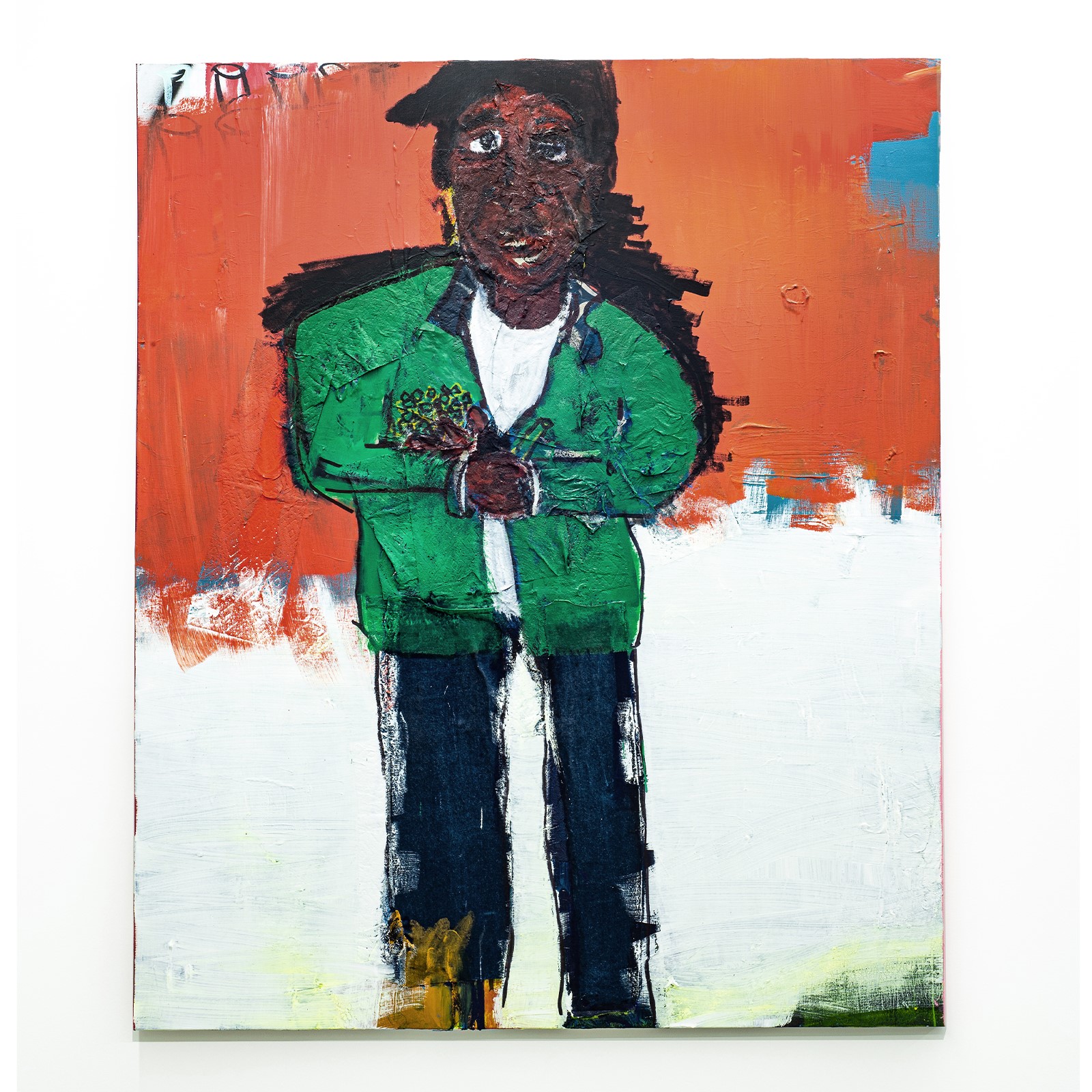

Roscoe Hall

Uncle Johnny (Circa 1991)

72 x 60 inches

Acrylic, denim, rayon, ink, pastel,

tears, and touch

2021

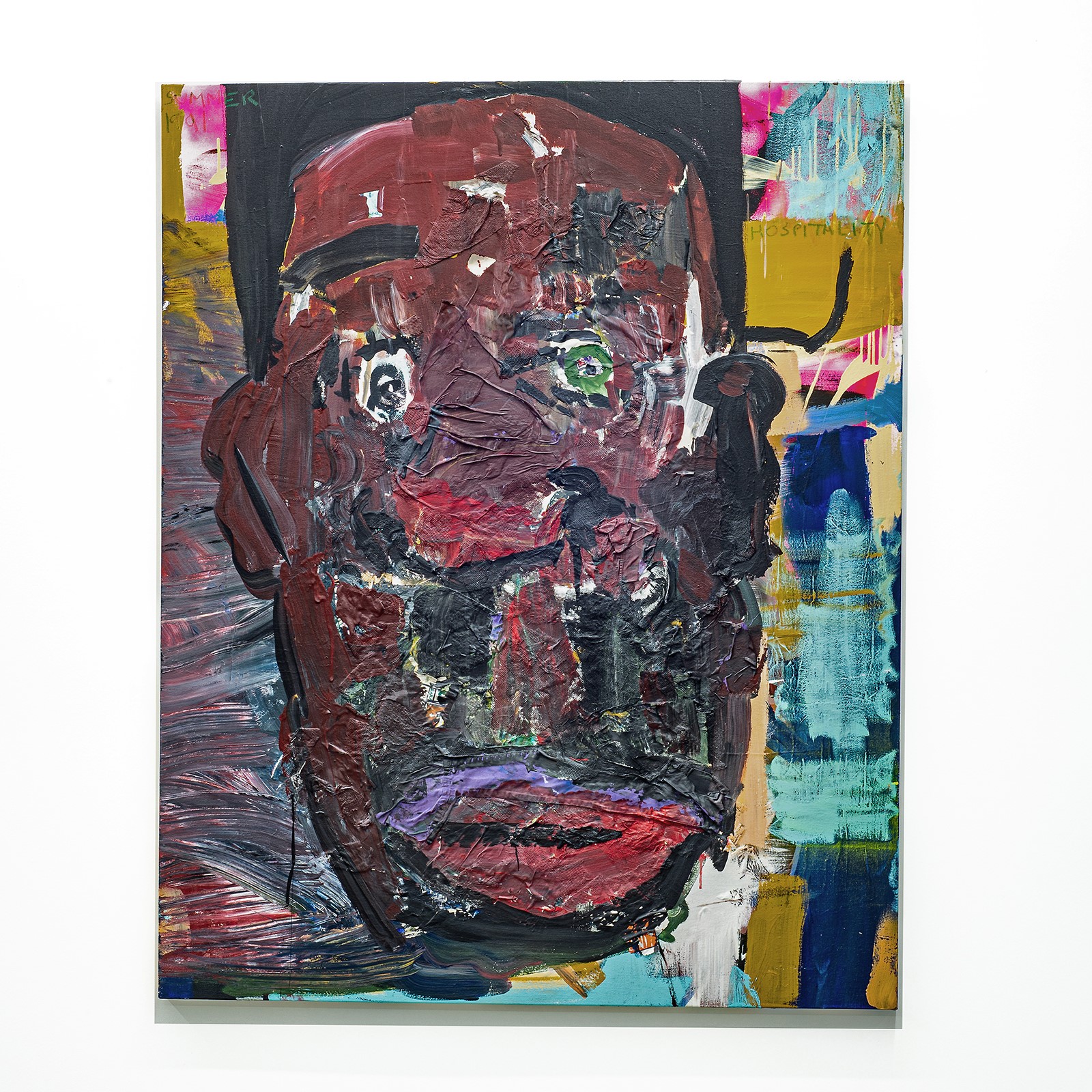

Roscoe Hall

Summer of 1991

60 x 48 inches

Acrylic, paper, rayon, pastels, sativa,

Hennessy, and lots of love

2021

Roscoe Hall

Knew It Was Real

60 x 48 inches

Acrylic, paper, pastels, and Benny Green

2021

Roscoe Hall

Morality Check

48 x 60 inches

Acrylic, ink, charcoal, pastels,

brandy’s newsiest album, german

beer, and Sativa

2021

Roscoe Hall

Alabama Blackbelt

48 x 60 inches

Acrylic, ink, charcoal, and love

2021